Obligatory Faceting Diagram

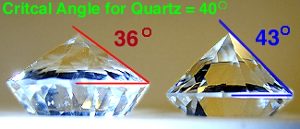

Anyone that ever writes about or publishes information on faceting is required to have this diagram. Go ahead find a book that doesn't have something very similar. Ok, so what does it mean? The diagram displays three stone profiles, and explains what happens when you cut a stone to far from the recommended facet angles. It is based on the Index of Refraction, and the far simpler law of reflection. Law of reflection, when a light strikes a flat surface the angle of incidence (the one ray going toward it) will be reflected at the same angle.

Now, realising that when light strikes a surface some will be reflected and some will be refracted. (Discussed previously.) The diagram above shows a stone cut below the CRITICAL ANGLE for a material. (A) - the light light entering the stone is refracted, but because the critical angle is not properly cut at the bottom of the stone, the light paths refracted back out of the stone.

In (b) we cut above the critical angle and near the recommended angle for the material, and thus the light entering the stone is first refracted, but then it is reflected by the bottom of the stone, and then reflected a second time, before exiting through the top of the stone. All in all a very desirable thing. This produces a lively stone.

In the third case (C), we have cut well above the critical angle, so we are safe as far as refraction is concerned, but upon hitting the bottom of the stone, the angle of reflection forces the light to hit the second side of the point and be refracted out again.